Chinese labor camp inmate tells of true horror of Halloween ‘SOS’

CNN

By Steven Jiang, CNN

(CNN) — Tree leaves were turning yellow and red in Damascus, Oregon, in late October. Competing with fall foliage for attention were Halloween decorations, which adorned almost every house in this sleepy middle-class suburb of Portland on America’s Pacific West Coast.

A few pumpkins sat on the steps leading to Julie Keith’s house, while three fake tombstones greeted visitors in the front porch — as they did last year.

“I feel obligated to use them every year now because I feel they need to have some worth,” said Keith, 43, who lives here with her husband and their two young children. “I am sad for the people who have to endure torture to make these silly decorations.”

The decorations came in a $29 “Totally Ghoul” toy set that Keith purchased in a local Kmart store in 2011. When she opened the package before Halloween last year, a letter fell out.

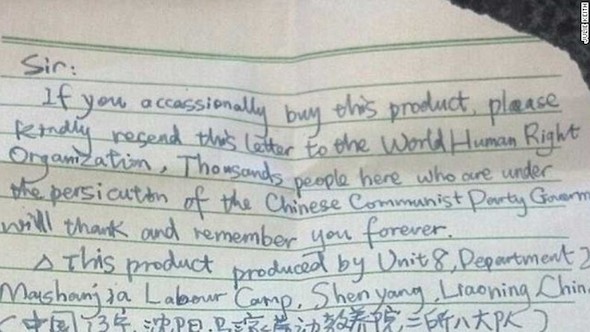

In broken English mixed with Chinese, the author cried for help: “If you occasionally (sic) buy this product, please kindly resend this letter to the World Human Right Organization. Thousands people here… will thank and remember you forever.”

Long hours, abuse

The letter went on to detail grueling hours, verbal and physical abuses as well as torture that inmates making the products had to endure — all in a place called Masanjia Labor Camp in China.

“It was surprising at first and I didn’t know if it was a hoax,” recalled Keith, a program manager at a company that runs a chain of thrift stores and donation centers. “Once I read the letter and researched on the Internet, I realized that this may be the real deal.

“I knew there are labor camps in China, but this slammed me in the face. I had no idea if this person was still alive or dead or in the camp — it’s extraordinary that it was able to come all the way from China.”

Keith heeded the writer’s call by reaching out to human rights groups but received no response. She then posted the letter on Facebook, which prompted the local Oregonian newspaper to run a front-page article.

As word of Keith’s unusual Halloween discovery spread, her story turned into international news, throwing a spotlight on one of China’s most notorious labor camps — and the controversial system behind them.

Strange discovery

Then one morning recently, some 6,000 miles away from Damascus, a bespectacled middle-aged Chinese man walked into the CNN office in Beijing to talk to us about this strange discovery half a world away. His voice was soft and calm but from time to time it would betray a hint of both agony and force.

“I saw the packaging and figured the products were bound for some English-speaking countries,” he said. “I knew about Christmas but we were making skulls and the like — I really didn’t know much about Halloween.

“But I had this idea of telling the outside world what was happening there — it was a revelation even to someone like me who had spent my entire life in China.”

After months of searching, through a trusted source and with some good luck, CNN found the man who says he wrote the letter that Keith found in her Halloween decorations. Released from the labor camp but afraid to be sent back, he agreed to his first television interview on the condition that CNN concealed his identity.

“Mr. Zhang” — as he would be called — is a follower of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, branded by the Chinese government as an evil cult and outlawed since 1999. He claims he was detained by police several months before the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and sentenced to two and a half years in the Masanjia labor camp in northeastern China.

“For people who have never been there, it’s impossible to imagine,” he said. “The first thing they do is to take your human dignity away and humiliate you.”

Zhang recounted the systematic use of beatings, sleep deprivation and torture, especially targeting those like him who refused to repent. Some gruesome details are too specific to him to be reported.

“Making products turned out to be an escape from the horrible violence,” he said. “We thought we could protect ourselves, and avoid verbal and physical assaults as long as we worked and did the job well.”

Secret messages

Moving forward with his plan to expose the horror in the camp, he secretly tore off pages from exercise books meant for political indoctrination sessions as inmates were barred from having paper. He also befriended a minor criminal from his hometown — a monitor for the guards — who managed to get him another banned item: a ball pen refill.

“I hid it in a hollow space in the bed stand — and only got time to write late at night when everyone else had fallen asleep,” he recalled. “The lights were always on in the camp and there was a man on duty in every room to keep an eye on us.”

Demonstrating his awkward position in bed, he continued: “I lay on my side with my face toward the wall so he could only see my back. I placed the paper on my pillow and wrote on it slowly.”

A college graduate, he said it took him two or three days to finish a single letter through this risky and painstaking process. “I tried to fill as much space as possible on each sheet,” he said. “Every letter was slightly different because I had to improvise — I remember writing SOS in some but not in others.

“Writing in English was very hard for me. I had studied the language but had never practiced speaking or writing much. That’s why I included some Chinese words to make sure the message would not be misunderstood because of my English mistakes.”

He slipped 20 letters into Halloween decoration packaging in 2008 and at least one, against all odds, got out and made headlines four years later.

Inside the camp

In late October, the autumn colors were fading fast in Masanjia Township as temperatures plunged to barely above freezing overnight. Driving towards town, the landscape was a mixture of barren farmland and mothballed factories with banners advertising cheap rent.

The town itself sits outside Shenyang, the provincial capital of Liaoning and an industrial base of eight million residents. If not for the labor camp infamy, it would be just another backwater in China’s northeastern rust belt.

A national emblem and two signs adorned an unguarded entrance in the center of town. One displayed “Liaoning Province Masanjia Labor” with the final word of “Camp” missing; the other read “Liaoning Province Ideological Education School.”

Inside the complex, which seemed to be closed — though officials would not confirm this — fields covered with haystacks and dried corn separated three clusters of low-rise buildings. Administrative offices were painted white, female inmates’ quarters mostly red and male’s largely beige. High blue concrete walls or green fences glinted with barbwire surrounding the inmate areas, as guard towers loomed above each corner.

“Wow, they’ve removed the sign in front the men’s camp,” marveled Liu Hua, pointing at an unmarked gate. “Look, that warehouse-looking building over there was where men like Zhang used to work.”

As the van carrying her and the CNN crew stopped near the women’s quarters, powerful memories rushed back to this 50-year-old farmer from a nearby village.

“I was confined in that building — Room 209,” she said while standing outside the fence. “We had the 4:15 a.m. wake-up call, worked from 6 a.m. to noon, got a 30-minute lunch and bathroom break, and resumed working until 5:30 p.m. Sometimes we had to stay up until midnight if there was too much work — and if you couldn’t finish your work, you would be punished.”

Last inmates

Liu only dared to return here after hearing that authorities had released the last group of inmates in mid-September — an apparent step toward shutting the facility down.

She had landed in Masanjia twice for petitioning against local officials over what she calls illegal land grabs. In total, she spent two and a half years in the labor camp. Her first stint overlapped with Zhang’s, but the two only met after both were released. Unlike Zhang, Liu didn’t see work as an escape. Remembering making down jackets bound for Italy and shirts sold to South Korea, she still shivers at the heavy workload that almost ruined her health.

“I had to do everything from matching fabrics to sorting materials and cutting loose threads,” she said. “Every day, I had to repeat seven work steps — for about 2,400 steps in total.”

Suffering from high blood pressure and malnutrition, Liu said she once fainted on the job but was denied medical care. For her defiant attitude, she said guards also ordered fellow inmates to beat her twice — their assaults with plastic stools and basins so vicious that she lost consciousness. “But I still had to work after I regained consciousness,” she added. “This place was Hell on Earth.”

Horror exposed

Last April, Masanjia’s fear-striking reputation was cemented when Lens, a Chinese magazine, published a lengthy article about the horrors inside its walls. Based on interviews with a dozen former female inmates including Liu, the story — titled “Leaving Masanjia” — detailed appalling working and living environments as well as frequent use of torture in the camp.

The Chinese journalists also spoke to two former officials at the camp who said Masanjia housed more than 5,000 inmates as free laborers at its peak and created annual revenues of nearly 100 million yuan ($16 million) — including those generated from exports.

Although the officials acknowledged poor living and labor conditions, they denied the use of torture. They admitted some officers may have used excessive force in dealing with disobedient inmates.

The story mentioned the discovery of an accusatory letter about Masanjia in a Halloween decoration package in the United States — and that the news caused a big stir in the labor camp. When asked, one official confirmed the letter indeed came from the Masanjia men’s camp.

The article’s publication surprised many observers, as domestic Chinese media — all state-run — had long shunned the sensitive subject.

Less than two weeks after the issue hit newsstands, the official state news agency, Xinhua, ran a response from the local authorities. Calling the article “seriously inaccurate,” provincial officials in Liaoning said their thorough investigation at Masanjia turned up no evidence of any torture or mistreatment of the interviewed inmates during their confinement.

Officials also rejected accusations of horrid living and working conditions in the camp, blaming the journalists for buying into “smear campaigns” launched by overseas Falun Gong movements. They did not address the Halloween letter in their rebuttal.

Lens magazine suspended publication for several months after its Masanjia issue.

Despite CNN’s repeated efforts, officials with Liaoning’s police department and press office declined to comment for this story.

Hundreds of camps

By all accounts, Masanjia is but one of hundreds of labor camps in China borne under the laojiao — or “re-education through labor” — scheme.

READ: City bids to end ‘Re-education Through Labor’ camps

Set up in 1957, the system allows the police to detain petty offenders — such as thieves, prostitutes and drug addicts — in labor camps for up to four years without a trial. China’s judicial process itself is already controlled by the ruling Communists in a one-party regime. In a 2009 report to a United Nations human rights forum, the Chinese government acknowledged 320 such facilities nationwide holding 190,000 people. Other estimates have put the number of inmates much higher.

Critics have long accused of the authorities of misusing the camps to silence so-called trouble makers, including political dissidents, rights activists and Falun Gong members.

“The continued existence of laojiao signifies China remains a police state,” said Pu Zhiqiang, a prominent Beijing-based lawyer known for defending government critics in court and a vocal opponent of the labor camp system. “It’s against China’s own constitution and laws, as well as international conventions it has signed.

“The danger is really about unrestrained police power at a time when they are under increasing pressure to maintain social stability.”

Two of Pu’s cases last year generated a massive backlash against laojiao, forcing the government to re-examine the thorny issue. In one case, a mother was sentenced to one and a half years in a labor camp for “disrupting social order” after she repeatedly petitioned officials to execute men convicted of raping her 11-year-old daughter. In another case, a young village official was sent to a labor camp for two years for retweeting posts deemed seditious.

Signs of change

Since the change of top leadership a year ago and despite mixed signals, the government may finally be ready to scrap the controversial system.

Li Keqiang, the new premier, said in his first press conference as head of the government that officials were “working intensively to formulate a plan” to reform the laojiao system and it may be announced before the year’s end. A senior Chinese diplomat repeated Li’s statement recently when addressing a U.N.-organized human rights forum.

While some activists have expressed concerns over the official term of “reform” instead of “abolition,” Pu, the lawyer, feels the strong tide of public opinions against the laojiao system has forced the government’s hands.

Already, provinces around China — including Liaoning — seem to be preparing for the inevitable. State media has cited examples of officials stopping accepting new inmates, changing camp names to drug rehabilitation centers and reducing staff on site.

And an empty Masanjia seems to be the ultimate testimony there is no going back.

Back in Oregon, Julie Keith is still awaiting the next move from her government. She contacted U.S. customs officials after finding the letter, as federal law prohibits the import of goods made by forced labor. She said officials admitted there was little they could do other than adding her report to their file. She hasn’t heard from them since.

Contacted by CNN, a spokeswoman with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) declined to confirm the existence or status of an investigation.

“These allegations are very serious and are an investigative priority for ICE,” she said. “These activities not only negatively impact the competitiveness of American businesses, but put vulnerable workers at risk.”

Supplying the West

Sears, the company that owns Kmart, also responded when asked how products in a labor camp in China ended up on its store shelves. “We found no evidence that production was subcontracted to a labor camp during our investigation,” it said, but added it no longer sources from this company.

Keith believes Sears “must know” but “would rather this be swept under the rug.”

Her skepticism is shared by human rights activists who have long called for stricter supervision of supply chains by multinational corporations. “A lot of these camps are run like businesses and, if you look online, there are a lot of them advertising,” said Maya Wang, a Hong Kong-based researcher for Human Rights Watch. “One would question how they get in touch with Western companies and whether or not Western companies have done due diligence when they procure services.”

For consumers, though, Wang says the only sure bet to avoid forced labor products from China is to push for legislation in their own countries and ensure strict implantation by their governments.

Even if China abolishes the labor camp system, experts like Wang and Pu point out that convicted criminals often work under similar labor conditions in prisons.

Freed from Masanjia but still haunted by the nightmare, Zhang has lived quietly in Beijing. When his long-forgotten letter was discovered by Keith and made news last year, he was as surprised as everyone else. He sent a new letter to Keith through a friend, thanking her profusely for her “righteous action that helped people in desperation achieve a good ending,” while reminding her that “China is like a big labor camp” under the Communist Party’s rule.

“It is quite ironic that it was a bloody graveyard kit that I purchased — knowing that the people who made these kits were desperate and bloody themselves,” Keith reflected.

“Now I check the labels and try not to buy things I don’t necessarily need, especially if it is made in China,” she added.

CNN’s David McKenzie contributed to this report.