Harvest of Horror: Falun Gong a Story that Belongs in Winnipeg Museum

11/26/2011

By: David Matas

Leo Tolstoy began the novel Anna Karenina by writing “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

One can say the same about human rights. Respect for human rights everywhere is alike. That is what the universality of human rights means.

Violations of human rights occur each in their own way.

Human rights standards and mechanisms teach us the same lesson everywhere about how to respond to atrocities. Each atrocity, though, teaches us something different about how to develop human rights.

Atrocities have a place in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, but not as histories or memorials. Rather they serve the purpose of teaching us how human rights have developed and should develop. The Holocaust has to be central to the museum not because it was a particularly awful tragedy, though it certainly was that, but because of its importance for the development of human rights standards and mechanisms, the breadth and depth of the lessons we have learned and can learn by focusing upon it.

On Nov. 28, I, alongside Maria Cheung, a professor in social work, and Terry Russell, a professor of Asian studies, will explain why we think the persecution of Falun Gong belongs in the museum. Our presentation is part of the University of Manitoba seminar series Critical Conversations, which is free, open to the public and held in the Faculty of Law (www.chrr.info).

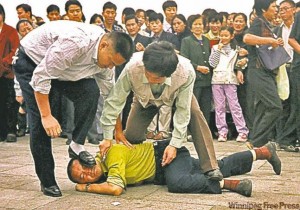

What does the persecution of Falun Gong in China teach us about human rights that we did not already know? Falun Gong is a set of meditation exercises with a spiritual foundation, a Chinese yoga, begun in 1992 and banned in 1999 out of Chinese Communist Party jealousy of its increasing popularity. Falun Gong practitioners were arrested in the hundreds of thousands and, if they recanted, released. Those who refused to recant, even under torture, disappeared.

David Kilgour and I have concluded in two reports and a book, Bloody Harvest, that these disappeared individuals have been killed in the tens of thousands for their organs, which are sold to transplant patients, often transplant tourists. I suggest we can draw these lessons from this experience.

— International human rights mechanisms work ineffectively in confronting human rights violations of a major power, particularly where that power has a veto in the Security Council, as China does.

— Governments, which juggle a wide variety of interests, have difficulty effectively pursuing a human rights agenda against a major economic and political power such as China, because pursuing that agenda may compromise their other interests.

— New technology developed for human benefit — in this case, transplant technology — can all too easily become a tool of repression and human rights abuse. Technology can change, but the human capacity for good and evil remains constant.

— The safeguards that need to be in place to prevent abuse of transplant technology are largely absent and need to be implemented in China and abroad.

— Preventing abuse of transplant technology engages a wide range of actors, many of whom historically have not had exposure to preventing human rights violations. For instance, transplant professionals, insurance companies providing coverage for transplantation abroad or pharmaceutical companies engaged in clinical trials of anti-rejection drugs in China.

— Allowing the military to engage in commercial enterprise in a country without the rule of law is a licence for human rights abuse. In China, the military is a conglomerate business that sells transplants to the public.

— Denial of access to statistical information can cover up human rights abuses. The release of death penalty statistics and transplant volumes, statistics that China now covers up, would make obvious what estimates now tell us: the volume of transplants far exceeds the volume of identified sources, primarily prisoners sentenced to death and then executed.

— Slave labour camps lead to other abuses besides slave labour. These camps are vast forced organ donor banks.

— Sourcing organs from prisoners sentenced to death is an abuse in itself and leads to other abuses, the killing of other prisoners for their organs who are not sentenced to death — in China, the Falun Gong.

— The Chinese capitalist variation of communist rule generates its own particular forms of human rights violations. The killing of Falun Gong for their organs, which are then sold for huge sums is the direct result of the communist repression and demonization of spiritual belief systems they cannot control plus the unbridled drive for profit without the rule of law.

Some of these lessons are not completely new. Yet, the repression of Falun Gong, even for the old lessons, gives new insights.

The list here, though not exhaustive, teaches us that by focusing on the repression of Falun Gong we can do more than help to end that abuse, as important as that is. We can learn how to improve human rights generally.

David Matas is an instructor in the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Law and an international human rights lawyer based in Winnipeg.

________________________________________________

The Learning Curve is an occasional column written by local academics who are experts in their fields. It is open to any educator from Winnipeg’s post-secondary institutions. Send 600-word submissions and a mini bio to julie.carl@freepress.mb.ca