A Transplant Conference Plays Host to China, and Its Surgeons Accused of Killing

[Photo Caption: The Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre will host The Transplantation Society’s 2016 conference, where the claimed reforms to China’s organ transplantation system will be given top billing. (Bill Cox/Epoch Times)]

The Transplantation Society’s biennial event, in Hong Kong this year, is the subject of complaints and boycotting for what critics call a lax stance on transplant ethics

In June, a report examining over 700 hospitals in China was published alleging that the Communist Party has been conducting a secret industrialized slaughter of prisoners of conscience for their organs. The researchers met with no substantive rebuttal, and key leaders in the international transplantation field have given a nod to some of its important conclusions.

The response from the global transplantation establishment has, however, been muted. Top transplantation officials did not express outrage, nor make known their concern over claims of transplant medicine being used as a new form of mass murder.

Nor did they submit polite questions to the Chinese authorities, enquiring about the origin of the surfeit of human organs that have fueled the massive, sustained surge of transplants in China since 2000. The report, authored by investigators Ethan Gutmann, David Kilgour, and David Matas, estimates that between 60,000 and 100,000 transplants were performed each year between 2000 and 2015, with the most likely source for the organs being prisoners of conscience.

Instead, when The Transplantation Society (TTS) holds its biennial conference in Hong Kong this August, China will be the star.

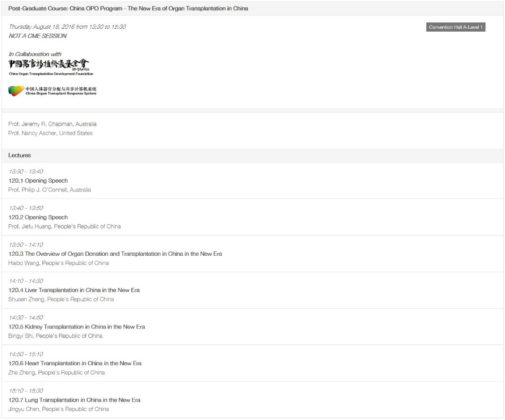

In sessions like “The New Era of Organ Transplantation in China” and “Transplantation Reform in China,” Chinese officials will have the opportunity to tell thousands of medical professionals at the industry’s foremost gathering that they have thoroughly reformed their system, basking in renewed global standing and legitimacy without having passed a single new law. And without a single doctor or official held to account for what has been described as genocide.

Ethical Questions

At the conference in August, two troubling issues stand out, say transplantation watchdogs. The first is that clinical research by Chinese doctors may have been based on organs obtained unethically. The second is that top TTS executives will be sharing a dais with the Chinese military doctors and transplant surgeons who are accused of engaging in the mass killing of innocents.

In the most remarkable case, one well-known Chinese doctor leads a bizarre double life: he is a top liver surgeon, but he also serves as a leader of the Communist Party’s agitprop organ dedicated to inciting hatred against Falun Gong, a persecuted spiritual practice that researchers say is heavily targeted for organ harvesting.

Allegations of organ harvesting from Falun Gong have dogged Chinese authorities for ten years, and have been met with varying levels of shock, disbelief, and skepticism in the global public sphere. Now, one of China’s prominent delegates will represent the nexus of these two fields of activity.

On the same panel as this surgeon, Zheng Shusen, sits Dr. Jeremy Chapman of Sydney, former head of TTS, current editor of the medical journal Transplantation, and long a personal friend to China’s top transplant official. Chapman also serves as the chair of the scientific program for the conference, granting him the task of ensuring that the abstracts from China did not use research based on organs from prisoners.

A review of over 50 presentations from China, conducted by Epoch Times, however, shows that at least a dozen fail to address the question of organ sourcing.

Unknown Organ Sources

Many of them do not provide any information about organ sourcing. For instance, one presentation, “Influencing Factors of Fatigue in Liver Transplant Recipients,” by Liu Hongxia of the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, provides no information about where the 285 livers came from, or when they were obtained, making it difficult to form a judgement about whether they were acquired ethically.

Other studies suffer a similar deficiency. “Pathological analysis of 544 cases of indicated renal allograft biopsies,” and another study on 658 kidney transplants, both presented by Wang Changxi, include kidney transplants performed beginning in 2010. As of 2009, China had only performed a total of 120 voluntary transplants,officials say. It is thus a distinct possibility that many of these transplants were involuntary.

Since 2005, Chinese officials have said that the vast majority of organ transplants come from executed prisoners; since 2013, a nationwide voluntary transplant system has existed, though reliable data about its operations is elusive.

Both of those presenters have a problematic history.

Liu, according to a journal article she co-authored in 2003, participated in at least 60 kidney transplants from January 1999 until May 2002. It is almost certain that none of these were voluntary, and it is statistically likely that many of them may have come from prisoners of conscience, given that such prisoners are believed to have been the primary source of organs in China since 2000.

The same issues exist for Wang, who performed over 700 kidney transplants, according to his hospital profile, the vast majority at a time when China had no voluntary donation system. Other presenters or co-authors boast of similarly problematic histories.

There are several other cases of presentations where no year of organ transplant is provided; in some cases, the years in question overlap with a period when China claimed to have a voluntary donation system (post-2013)—though not all are of this sort.

Even after 2013, given the continued use of organs from executed prisoners and prisoners of conscience, it is impossible for outsiders—including international transplant experts—to know for sure which research comes from organs obtained voluntarily, and which from executions.

‘Very Detailed Analysis’

When approached with questions about the abstract selection process, Dr. Jeremy Chapman wrote in an email: “We undertook a very detailed analysis of all submitted papers using a group of highly experienced individuals with detailed knowledge of China transplant programs … Any papers that included any donor/transplants that were potentially from executed prisoners were rejected.”

Chapman is editor-in-chief of The Transplantation Society’s official journal. Upon receiving a spreadsheet highlighting the dozen potentially problematic abstracts, along with questions about how the organ sourcing in them was verified, Chapman made clear that he and his colleagues had put trust in their Chinese counterparts to ensure compliance with ethical norms. Chinese presenters were required to assure the congress “on three occasions in writing” that organs were sourced ethically.

Chapman added: “All submissions in which executed prisoner organs were possibly used have been rejected, as have all submissions where there has been no response to any of our requests for declaration.” He did not respond to a query about how many abstracts were rejected.

The lack of verification has troubled some.

“I have reviewed many scientific abstracts for many meetings over 28 years,” wrote Dr. Maria Fiatarone Singh, a board member of Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting (DAFOH), in an email. “The only thing reviewers get is a 250-word abstract and the names of the authors and institutions. … Nothing could have been verified beyond what is in those 250 words.”

Fiatarone Singh and her colleagues at DAFOH have lodged their discontent with the fact that the congress in Hong Kong, including presenters and other panelists, will be heavy with doctors who have long been involved in what they regard as crimes against humanity.

Doctors Accused of Being Killers

“Despite mounting international concerns, TTS has booked China’s leading transplant expert, Huang Jiefu, as a plenary speaker at the upcoming transplant congress,” DAFOH wrote in a recent press release.

“Under his tenure as deputy minister of health, China’s transplant numbers grew exponentially, coinciding with the nationwide outbreak of persecution and detention of prisoners of conscience after 1999, and reports of forced blood testing and medical examinations of detained Falun Gong practitioners targeted for their beliefs,” the group wrote.

Huang Jiefu himself is implicated in China’s kill-on-demand organ transplant system. According to Chinese media reports, he has performed hundreds of liver transplants over the years. In 2005, from a hospital in Xinjiang, he put out an urgent call and obtained two livers within 24 hours, flown to him overnight. Though this required the killing of two people, in the end the livers were not even used.

One of the most problematic doctors to co-author a paper at the congress is Shen Zhongyang.

Shen is the industrious surgeon behind Tianjin First Central Hospital, a transplant facility that has been the subject of significant scrutiny for both its tremendous volume of transplants, and for its boldness in advertising its services to an international audience.

This hospital was the subject of an 8,000-word investigation by Epoch Times in February 2016 which found that its transplant volume could not possibly be accounted for by death row prisoners, and that another organ source must have been relied upon.

Shen is the co-author of a paper that will be presented in Hong Kong about techniques for measuring livers.

But another surgeon attending the conference should give even greater pause: Dr. Zheng Shusen.

Zheng Does Double Duty

Zheng Shusen has personally performed at least hundreds of liver transplants, and has overseen thousands. From his base at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, he co-authored a 2005 paper about the rapid acquisition of livers, called “emergency transplants,” for patients suffering acute liver failure.

In the absence of a voluntary, national matching system like those existing in other countries, this can only mean that fresh donors were identified locally and killed within as short a period as 24 hours. Researchers have pointed to such rapid organ acquisitions as key evidence that a pool of live donors is kept on standby, waiting to be harvested.

Meanwhile, Zheng leads a double life. When not performing emergency liver transplants, he leads anti-Falun Gong indoctrination seminars, as head of the Zhejiang Anti-Cult Association.

Zheng assumed his role as chairman of the Party-run NGO in 2007. Since then, he has addressed schools and government work units, edited book volumes, and presented awards, all aimed at vilifying Falun Gong, a traditional Chinese spiritual practice that has been persecuted since 1999.

Researchers believe that soon after Falun Gong practitioners were defined as the Party’s number one political enemy, and thus placed outside the protection of the law, they were targeted for organ harvesting—a lucrative activity conducted with impunity by China’s medical-military complex.

Anti-Cult Associations around China have played an instrumental role in the anti-Falun Gong campaign. They perform two tasks, according to records of their activities online: The first is to incite hatred against the practice; the second is to develop the curricula and training sessions for frontline ideological re-education. This refers to attempts to force Falun Gong practitioners to renounce their beliefs and pledge allegiance to the regime. Victims describe it as a harrowing experience that involves isolation, demands of submission to Party will, and physical torture.

According to records online, Zheng chaired an “anti-cult” cadre training program at the Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power in October 2010. He gave the opening address while seated alongside the head of the Zhejiang 610 Office, the extralegal security agency in charge of imprisoning and torturing Falun Gong practitioners.

Discovering this other side of Zheng’s identity requires Chinese-language research, and a sensitivity to the highly politicized institutional context in which transplantation exists in China. This is an awareness that TTS leaders lack, according to the organization’s critics.

All Prisoners Are Equal

But even after TTS officers were apprised of the hidden identities of their Chinese counterparts, no changes to the congress lineup were made.

Zheng will appear on a panel alongside Chapman, current TTS president Philip O’Connell, and the organization’s incoming president, Nancy Ascher. Other panelists include Huang and the prolific military transplant surgeon Shi Bingyi.

Zheng will give a speech titled “Liver Transplantation in China in the New Era.”

Ascher did not respond to a research note emailed to her apprising her of the identity of her co-panelist; Chapman similarly declined to comment. O’Connell, copied by his colleagues in responding emails, also refrained from commenting.

TTS’s ethics guidelines on dealing with Chinese doctors, formulated by the organization’s leadership, have for years aimed to balance two goals: on the one hand, the imperative to uphold their own ethical standards, and the other to “promote dialogue” and “educate” Chinese doctors about “alternatives to the use of organs and tissues from executed prisoners.”

Traditionally, Chinese doctors have been permitted to become TTS members and to give presentations at its congresses—as long as the research itself is clean.

These ethical deliberations, however, have only addressed doctors who have used organs from death row prisoners.

What if the doctor, like Zheng, is reasonably suspected of killing innocents for their organs?

According to TTS, it makes no difference—a doctor like Zheng is free to take part in the conference.

In China, it is legal, although ethically problematic, to take organs from consenting executed prisoners. … It is not overtly legal to murder people for their organs.

“We wish to highlight that the ethical principles which form the basis of TTS policy regarding the procurement of organs from executed prisoners should be understood as also applicable to the procurement of organs from any person who is not able to provide valid consent–voluntary, informed, and specific–hence including prisoners of conscience,” wrote Dr. Beatriz Domínguez-Gil, the chair of the Ethics Committee.

This obliterates the moral gulf between the two, ethicists say.

“In China, it is legal, although ethically problematic, to take organs from consenting executed prisoners,” wrote Wendy Rogers, a bioethicist at the University of Macquarie in Sydney, in an email. “Even in China, it is not overtly legal to murder people for their organs.”

She added: “Doctors participating in the former might be accused of unethical practice, but doctors in the latter category are criminal murderers. We generally make an ethical distinction between murderers and others. Any ethical theory I can think of would make this distinction.”

Boycott

The ethical slope descended by TTS has left some prominent members at a loss. Dr. Jacob Lavee, president of the Israel Transplantation Society, the country’s most prominent heart transplant surgeon, and a member of TTS’s Ethics Committee, will not be flying to Hong Kong.

“I have tried and failed to persuade TTS leadership to refrain from moving the TTS 2016 Congress, originally planned to be conducted in Bangkok, to Hong Kong,” he wrote in an email.

Providing China a global platform, while ignoring reports of organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience “is a moral stain on TTS ethical code,” he wrote.

Lavee continued: “The amazing finding of so many ethically doubtful presentations in the congress’ scientific program is just another aspect of the disintegration of the moral fiber of my society. I have therefore announced to my colleagues that I will boycott the Hong Kong meeting, and have called upon them to follow me.”