Report: Up to 1.5 Million Killed by Chinese Regime for Their Organs

WASHINGTON—Transplant surgeons in China are awash in human organs. Some complain of working 24-hour shifts, performing back-to-back transplant surgeries. Others ensure they’ve got spare organs available, freshly harvested—just in case. Some hospitals can source organs within just hours, while others report transplanting two, three, or four backup organs, when the first fails.

All this has been taking place in China for over a decade, with no voluntary organ donation system and only thousands of executed prisoners—what China says is its official organ source. In phone calls, Chinese doctors said the real source of organs is a state secret. Meanwhile, practitioners of Falun Gong have disappeared in large numbers, and many have reported being blood tested while in custody.

An unprecedented report by a small team of relentless investigators was published on June 22, documenting in sometimes astonishing detail the ecosystem of hundreds of Chinese hospitals and transplant facilities that have been operating quietly in China since around 2000.

Collectively, these facilities had the capacity to perform between 1.5 and 2.5 million transplants over the last 16 years, according to the report. The authors suspect the actual figure falls between 60,000 and 100,000 transplants per year since 2000.

“The ultimate conclusion of this update, and indeed our previous work, is that China has engaged in the mass killing of innocents,” said co-author David Matas upon the report’s launch at the National Press Club in Washington on June 22.

The study, titled “Bloody Harvest/The Slaughter: An Update,” builds on the previous work of the authors on the topic. Released shortly after the passage of an official censure of organ harvesting in China by the U.S. House of Representatives, the research poses an explosive question: Has large-scale medical genocide been taking place in China?

Big Profits

The People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, whose main task is to provide health care for top Communist Party and military officials, is among the most advanced and well-equipped hospitals in China. The number of organ transplants it performs is a military secret—but by the early 2000s, its clinical division, the 309 Hospital, was making most of its money from them.

“In recent years, the transplant center has been the primary profitable health care unit, with gross income of 30 million yuan in 2006 to 230 million in 2010—a growth of nearly eightfold in five years,” its website states. That’s a jump from US$4.5 million to US$34 million.

The PLA General Hospital wasn’t the only health care institution to stumble across this lucrative business opportunity. The Daping Hospital in Chongqing, affiliated with the Third Military Medical University, also managed to boost its revenue from 36 million yuan in the late 1990s, when it had just started performing transplants, to nearly 1 billion in 2009—a growth of 25 times.

Even Huang Jiefu, China’s spokesman on organ transplantation, stated to the respected business publication Caijing in 2005: “There’s a trend of organ transplantation becoming a tool for hospitals to make money.”

How these remarkable feats were achieved in so short a time across China, when there was no voluntary organ donation system, when the number of death row prisoners was decreasing, and where the waiting times for patients expecting transplants could sometimes be measured in weeks, days, or even hours, is the subject of the new 817-page (including citations) report.

Parts of the report, drawing from whistle blower testimonies and Chinese medical papers, state that some donors may not have even been dead when their organs were removed.

“This is extremely difficult research to have done,” said Li Huige, a professor at the medical center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany, and a member of the Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting advisory board, after reviewing the study.

The report contains a forensic tally of all known organ transplantation centers in China—over 700 of them—and counts their bed numbers, utilization rates, surgical staff, training programs, new infrastructure, recipient waiting times, advertised transplant numbers, use of anti-rejection drugs, and more. The authors, armed with this data, estimated the total number of transplants performed. The number stretches past 1 million.

This conclusion, though, is only half the story.

“It’s a mammoth system. Each hospital has so many doctors, nurses, and surgeons. That in itself isn’t a problem. China’s a big country,” said Dr. Li, in a telephone interview. “But where did all the organs come from?”

Captive Bodies

Organs for transplant can’t be removed from dead bodies and simply placed into storage until needed: They need to be recovered before or soon after death, and then quickly implanted into a new host. The often desperate timing and logistics around this process make organ matching in most countries a complex field, with waiting lists and dedicated teams who encourage family members of accident victims to donate organs.

But in China, the donors seem to be captive, waiting around for the recipients.

Changzheng Hospital in Shanghai, a major PLA medical center, reported performing 120 “emergency liver transplants” as of April 2006.

The term refers to when a patient with a life-threatening condition is admitted to the hospital or transplant ward, and a matching organ is found within only hours or days. This is rare in other countries.

But Changzheng Hospital published a paper in the Journal of Clinical Surgery, a Chinese medical journal, about its success with emergency transplants. “The shortest time for a patient to be transplanted after entering the hospital was four hours,” it stated.

In a one-week period from April 22 to April 30, 2005, the hospital performed 16 liver and 15 kidney transplants.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University published its own study in a similar vein, documenting that between early 2000 and late 2004, 46 patients received “emergency liver transplants”—meaning that recipients were all matched with a donor within 72 hours.

Even the official China Liver Transplant Registry, in a set of slides presenting its 2006 annual report, compares the number of “selectively timed” transplant surgeries with the emergency transplants. There were 3,181 regular transplants in the year, and 1,150, or just over a quarter, were made under emergency matching conditions.

These phenomena are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to explain according to official pronouncements. And they stand as prima facie evidence that a captive donor population is on standby for its organs to be harvested.

“This is very emotive for me,” said Wendy Rogers, an Australian bioethicist at Macquarie University, whose close friend suffered liver failure due to hepatitis and needed a transplant within three days if she was to live.

“She was extraordinarily lucky to get one in that timeframe,” Dr. Rogers said.

“But to do 46 of them in a row? It’s hard to think of another plausible explanation, apart from killing on demand.”

Parts of the report, drawing from whistleblower testimonies and Chinese medical papers, state that some donors may not have even been dead when their organs were removed. This includes the testimony of a former paramilitary police officer, who said he witnessed a live harvest operation conducted without anesthesia, and that of a former health care worker in Jinan.

Targeted for Elimination

The authors of the new report, relying on previous evidence and new findings, contend that the primary population in China that could have been targeted in this way are prisoners of conscience, composed primarily of practitioners of Falun Gong.

Falun Gong is a traditional discipline of the Buddhist school that became extremely popular in China throughout the 1990s. It involves doing five meditative exercises and living according to teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. The state tacitly supported Falun Gong, and an official survey indicated there were upward of 70 million practitioners by 1999—more than the number of members in the Communist Party.

In July 1999, the leader of the regime, Jiang Zemin, unleashed a national campaign to eliminate the practice. He initially met with high-level opposition, but quickly turned the anti-Falun Gong mobilization into a means of consolidating his power within the Party, as he promoted loyalists and sidelined resisters.

Organ harvesting as a means of eliminating the Falun Gong population appears to have begun by the following year.

The evidence that this has been taking place has been available for a decade now—but this is the first time the estimated death toll has been so formidable, the sheer volume of evidence so overwhelming, and the central role of the state as enabler so clear.

The three authors of the report—David Kilgour, David Matas, and Ethan Gutmann—have previously published reports on the topic, but this is the first time they have joined forces. Even they were surprised by the results of the study.

“When you were a kid, did you ever pick up a big rock and see all this life underneath it—ants and insects? That’s what the experience of working on this report has been like,” said Gutmann, a journalist whose book on the topic, “The Slaughter,” was published in 2014.

Kilgour is a former Canadian parliamentarian and Matas is a well-known human rights lawyer; the pair published a book on the topic, “Bloody Harvest,” in 2009, which followed a groundbreaking report by the same name released in July 2006.

In the last few years, researchers of transplant abuse in China had largely been under the impression that the scale of organ harvesting had retreated considerably, or at least that Falun Gong practitioners and other prisoners of conscience were no longer targeted.

The authors discovered this was not so. “They’ve built a juggernaut,” Gutmann said. “We’re looking at a gigantic flywheel, which they can’t seem to stop. I don’t believe it’s just profit behind it, I believe it’s ideology, mass murder, and the cover-up of a terrible crime where the only way to cover up that crime is to keep killing people who know about it.”

The backbone of the report, and its single largest section, is an exhaustive account of every hospital in China that is known to perform transplants. Of the 712 hospitals that are identified, 164 are given detailed, individual treatment in the report.

Centers of Harvesting

The Nanjing General Hospital, in the Nanjing Military Command, for instance, is given two pages. The report discusses the prolific career of Li Leishi, the founder of the kidney research center at the hospital; there was even a Communist Party document that made it mandatory to study the “model” he had established. Li was commended by the regime for building one of the fastest growing kidney transplant centers in the country.

In a 2008 interview, Li, then 82 years old, said that in the past he typically performed 120 kidney transplants a year, but now does only 70. Another chief surgeon was reported to be performing “hundreds of kidney transplants a year” as of 2001. With 11 chief and six associate surgeons engaged in kidney transplants, the total volume of transplants at the hospital may have reached around 1,000 annually, the report states.

Astonishing transplant volumes like this appear throughout the report.

At Fuzhou General Hospital, also in the Nanjing Military Command, Dr. Tan Jianming had personally directed 4,200 kidney transplants as of 2014, according to his biography on a website belonging to the Chinese Medical Doctor Association.

The Xinqiao Hospital, affiliated with the Third Military Medical University, in southwest Chongqing, said it had performed 2,590 kidney transplants by 2002, including 24 in a single day.

Zhu Jiye, director of the Peking University Organ Transplant Institute, said in 2013: “There was one year in which our hospital did 4,000 liver and kidney transplant operations.”

In a June 2004 paper published in the Medical Journal of the Chinese People’s Armed Police Forces, a handy table is provided that notes that the Beijing Friendship Hospital and the Guangzhou Nanfang Hospital had conducted more than 2,000 kidney transplants by the end of 2000. Three other hospitals each recorded performing 1,000 by the end of that year. Most of these must have been performed only in a year or so, given that up until the end of the 1990s, transplantation in China was a boutique medical niche.

Hospital after hospital, page after page, volume figures like this are laid down, sourced back to official Chinese publications, including speeches, internal newsletters, hospital websites, medical journals, media reports, and more.

Without exception, these hospitals only discussed such impressive volume figures beginning in the year 2000. The massive infrastructure development and surgeon training programs also only began to be reported then—soon after the onset of the persecution of Falun Gong.

State Killing Machine

The Chinese regime’s official line on its organ sources has shifted over time. In 2001, when the first defector emerged from China claiming that the regime was using death row prisoners as an organ source, official spokesmen denied it, claiming that China relies primarily on voluntary donors.

In 2005, officials began hinting that death row prisoners were used instead. And after allegations of organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners were made public, in 2006, Chinese officials insisted that death row prisoners, who consented to having their organs removed after death, were the primary source.

But the menacing conclusion that slowly emerged through the research published in the report—which includes nearly 2,000 footnotes—is that the entire industry was deliberately created, almost overnight—right after an abundant new organ source became available.

This is suggested by the immense state involvement, both at the central and local levels, in the industry. Beginning in the 1990s, China’s health care system was largely privatized, with the state only paying for infrastructure, while hospitals had to finance themselves.

The liver transplant center at Renji Hospital saw a leapfrogging number of transplant beds: from 13 in late 2004, to 23 only two weeks later, to 90 in 2007, to 110 in 2014.

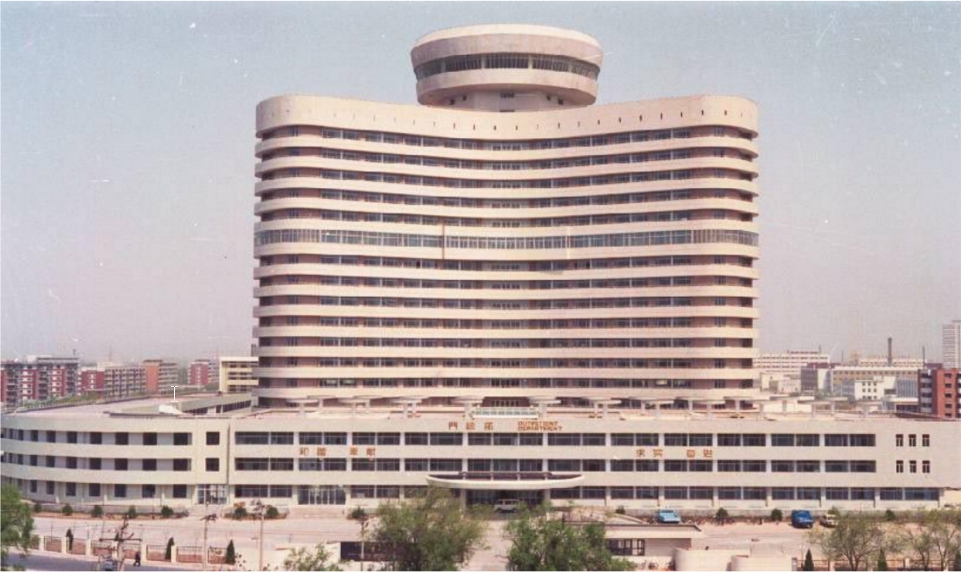

In 2006, Tianjin First Central Hospital added an entire 17-story building, with 500 beds, just for organ transplants. There are many other such cases; the report contains photographs of the often impressive buildings.

Organ transplantation quickly became a profitable business, and the central and local governments underwrote research and development, the construction of palatial new transplant facilities, and funded doctor training programs, including the overseas training of hundreds of transplant surgeons.

An entire industry of Chinese-made anti-rejection drugs came online, while Chinese hospitals began developing their own preservative solutions, chemicals in which organs are kept while being transported between the donor and the recipient.

As the transplant center associated with China Medical University in Shenyang said on its website: “To be able to complete such a large number of organ transplant surgeries every year, we need to give all of our thanks to the support given by the government. In particular, the Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, Public Security system, judicial system, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Civil Affairs have jointly promulgated laws to establish that organ procurement receives government support and protection. This is a one-of-a-kind in the world.”

The authors of the report have declined to give a death toll. While it is possible that in some cases multiple organs came from a single victim, until 2013 China had only an ad hoc and localized matching system. Chinese surgeons have also complained about the great wastage in China’s transplant industry, where often only one organ comes from one donor. Thus, if 60,000 to 100,000 transplant surgeries were performed annually, the death toll of organ harvesting in China may stretch to 1.5 million.

As China Medicine Report wrote in a late 2004 summary of the transplant industry: “Currently, because China has no interactive organ registration system, sometimes only a kidney is taken from a donor and many other organs are simply wasted.”

Matas, at the press conference on June 22, said: “The phenomena of multiple organs from one person has been happening, but in a statiscally insignificant way.”

According to Lan Liugen, the deputy director of surgery at the PLA’s No. 303 Hospital in Guangxi Province, as of early 2013 there were only two hospitals in China that could procure and transplant multiple organs from a single donor. “Such surgeries are the best use of donor resources,” he said. “Currently only countries like the United States, Germany, and Japan can do multiple organ transplants from the same donor simultaneously.”

The authors are publishing their findings at a time when the climate of opinion on this issue seems poised for a shift: Journalists are more willing to look into the topic; documentaries on it are being produced and winning awards; and the number of transplant doctors and ethicists who are learning about China’s transplant system, and who are appalled by it, is growing.

Recently, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution expressing concern about China’s practices, with House members denouncing them as “ghoulish” and “disgusting.”

A 2015 documentary titled “Hard to Believe,” now screening on PBS stations, explores how the issue has been received by the fields of journalism and medicine. The gravity of what has taken place in China for a decade and a half is only now beginning in sink in. (Disclosure: Epoch Times’s Matthew Robertson, the author of this article, was interviewed for the documentary.)

Rogers, the Australian bioethicist, says she has found that others have difficulty taking in what is happening in China.

“I had to explain it in detail to a German friend who’s a bioethicist, who deals with many challenging international topics,” Rogers said. “She literally couldn’t believe me, and asked, ‘Why didn’t I know about this already?’”