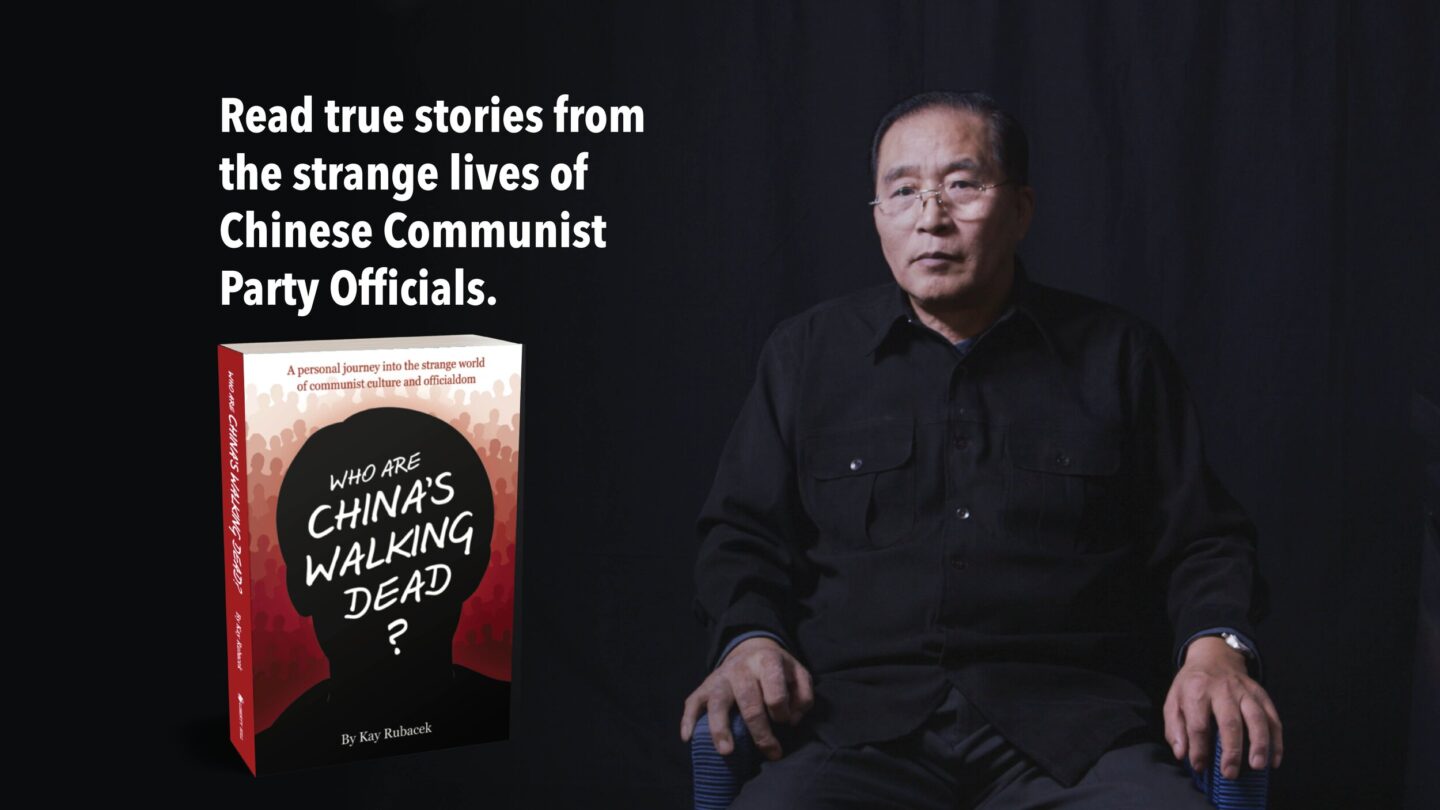

‘Who Are China’s Walking Dead?’ Book Review

Filmmaker Kay Rubacek’s book “Who Are China’s Walking Dead” is as dystopian as the title suggests; however, it doesn’t feature kitschy zombie novel tropes, but rather describes, without pulling punches, the reality of life—if one can call it that—in China today.

In a country where senseless death, lack of accountability, and commoditization of human life are so prevalent, jaw-dropping events happen in China every minute without so much as the batting of eyes, and everyone has a tragic story.

The book was born when Rubacek interviewed former Chinese Communist Party members for her film “Finding Courage,” a documentary about a California family trying to recover the remains of a sister who was tortured to death in one of China’s reeducation camps, because of her faith in Falun Gong.

She spoke to Chinese professors, businessmen, and retired officials in an effort to understand the other side—that of the communist party, the persecutor.

In those conversations, she uncovered a cultural divide, not like that which exists between America and England, nor even between America and Papua New Guinea, but of opposing realities—a twisted form of logic and moral relativism so blatant as to induce speechlessness.

This is the gap that “China’s Walking Dead” bridges.

For anyone who claims the right to have an opinion on world events, it’s essential to read and understand this book. Decades of foreign policy have been made with the underlying assumption that the Chinese are just like us, in essence: they love their families and want a better life, they crave freedom and dignity as any human does. But, the excuse goes, China needs to develop a bit more before it can afford human rights—such is the song of the apologist.

While basic human desires may be universal and true, the degree to which Chinese citizens under communism have been dehumanized is hard to imagine when you don’t force yourself to look.

Rubacek has Russian grandparents who warned her of these hard truths, but many American sons and daughters of survivors lack this benefit—traumatic experiences like communism and rape can be difficult to speak about after the fact. By being open and genuinely curious, Rubacek has brilliantly succeeded in inviting Chinese officials to relate their experiences in a way that Western readers can understand, if not identify with.

Where the gap was too wide to bridge, Rubacek composed an informal glossary. With Mainland Chinese, doublespeak is a pervasive phenomenon, an integral feature of Party culture. To help herself and us navigate this, she noted some of her own working definitions throughout the chapters.

Understanding the persecution of Falun Gong—the subject of Rubacek’s original quest—is essential to understanding the mindset of communist leadership, as well as the societal structure that fosters and allows it. So often, when people learn the facts about the persecution—that Falun Gong is an apolitical group of spiritual meditators, that it was widely beloved among Chinese in the ’90s, and that overnight the group was demonized and slaughtered in the thousands—the most common and understandable query is, “But why?”

The reality presented in “China’s Walking Dead” is a first step toward answering that question. Let go of any assumptions about rule of law, the consent of the governed, and other niceties we in the West are fortunate to have, and read this book.

Available on Audible, Amazon, and as an Ebook on SwoopFilms.com

Please support Friends of Falun Gong when shopping on Amazon by choosing FoFG as your charity on Amazon Smile.